Intervju med Josiah Howard - författaren till Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide

Foto taget av Kamron Hinatsu

Josiah Howard är författaren till Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide och är världens ledande expert inom ämnet blaxploitation. När jag bestämde mig för att ha en temavecka kring genren kontaktade jag honom nästan omgående angående möjligheten att få intervjua honom. Jag fick ett vänligt och upplyftande svar inom 24 timmar och började genast jobba på frågorna jag skulle ställa till honom.

How and when were you first introduced to the blaxploitation genre and why do you think it had such a lasting effect on you?

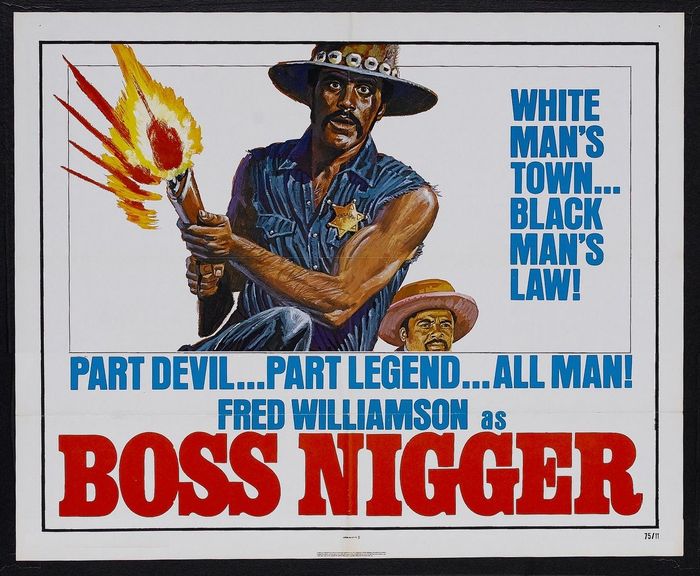

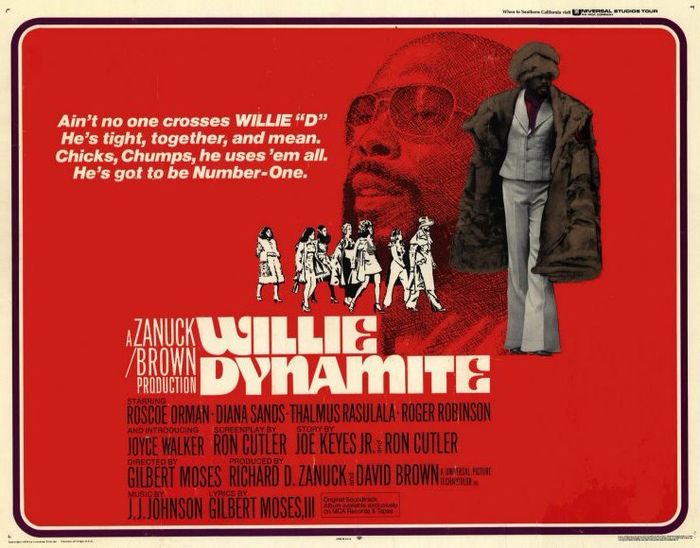

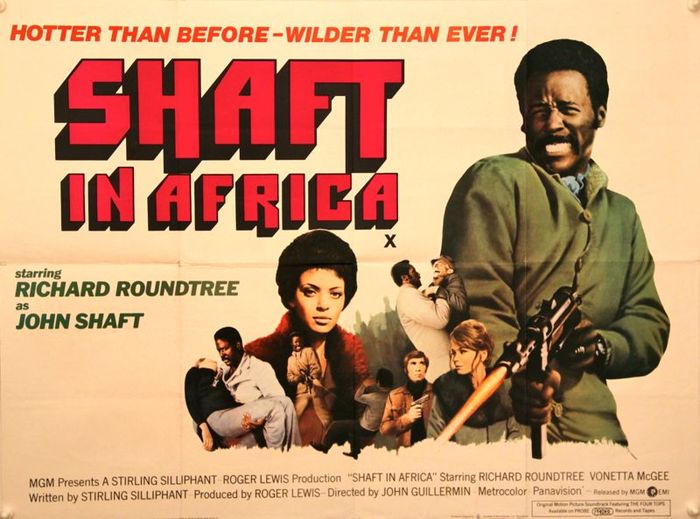

I first became fascinated by the films through their bombastic poster art. In the seventies the promotion was everywhere; on movie marquees, on public transportation and, of course, in newspapers and magazines. I had never seen young black people with large Afros and Bell Bottoms toting sawed off shotguns before. It was pretty exciting! I was too young to go and actually see the movies at the time but I was obsessed with the posters. I was the first kid at the theater when they changed the posters each week!

I first became fascinated by the films through their bombastic poster art. In the seventies the promotion was everywhere; on movie marquees, on public transportation and, of course, in newspapers and magazines. I had never seen young black people with large Afros and Bell Bottoms toting sawed off shotguns before. It was pretty exciting! I was too young to go and actually see the movies at the time but I was obsessed with the posters. I was the first kid at the theater when they changed the posters each week!

What do you think it is about blaxploitation, which is a genre very much of its time, that still appeals to audiences today, including honkies like myself who weren’t even born when they were made?

The pictures are timeless because the stories are about people wanting to make their dreams come true: by whatever means possible. The only difference is the presentation. Most of the characters in blaxploitation films operate outside of the law and are African American. But the dream is the same for everyone, everywhere. Additionally, the pictures are cultural artifacts: windows into the 1970s American experience.

Censorship on any level is always the wrong way to go. I think changing the title of a film—which is a creative work; a piece of art—is like going to a museum with a paint brush and saying “I can make this painting better” and painting over it. The titles of blaxploitation films are written in time and should remain as such. I understand the new politically correct climate that we live in and I think political correctness has its place but I also stand by the intent of the distributors making decisions that better position them to sell entertainment product. If the safer re-titling of the films expands the audience, that’s a good thing.

The publisher—Plexus Books—and I both agreed that the Hit Man image would be a great book cover. You not only get the black man with the funky clothes and the gun, you also get a bulls-eye; a target! It made a visual impact. For a while we considered Coffy, but that image is over circulated. We wanted something new and relatively unseen.

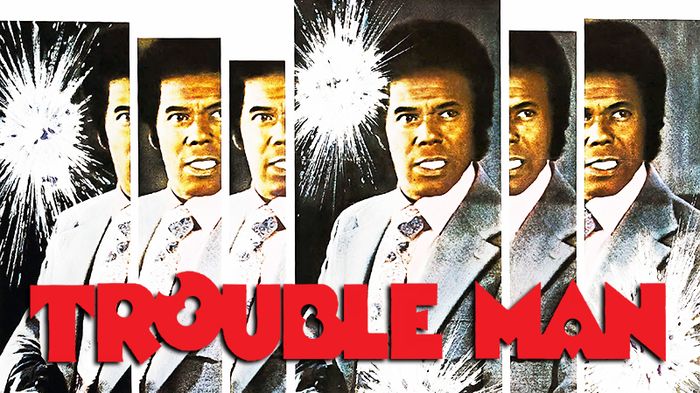

If I had to pick a favorite blaxploitation move poster it would be 1972’s Trouble Man. I love the fractured mirror image illustration. The colorful repetition and the use of gunshot holes in the calligraphy is thrilling. Of course that’s also a detail in the Blaxploitation Cinema cover art. It says: “there’s been a shooting here; pay attention, watch out!”

In the review section of your book, you include Black Mama, White Mama, The Big Doll House, The Big Bird Cage and Women in Cages. I've personally never viewed those particular movies as blaxploitation because I don't think they offer a lot of components found in the genre, apart from being made in The Philippines like other blaxploitation movies and starring Pam Grier. I view them as strictly Women in Prison movies. Can you make a case for them belonging to the blaxploitation genre?

My criteria for categorizing a film as blaxploitation is straightforward. I define the films as theatrically released motion pictures (between 1970-1980) that were conceived, green lit and first and foremost promoted to inner city black audiences. Using this broad definition, which I more thoroughly outline in Blaxploitation Cinema, many “gray area” pictures make the cut. Many film fans don’t believe that Mahogany and Greased Lightening, should be in the book, but I beg to differ—and it’s an ongoing argument!

Blaxploitation films are really “exploitation” films; that’s where the hybrid name comes from. They’re low budget pictures made for the Drive-In and “downtown” theater market. Black people experienced films like The Big Doll House and Women in Cages as a Blaxploitation film—not as a Woman in Prison film. Additionally blaxploitation films were often shown on Double Bills. This under-discussed approach to distribution should also be considered. If you went to the theater to see two pictures and one was clearly defined as Blaxploitation (40 of the films have the word “black” in the title by the way), what was your experience of the accompanying film? Why were they paired? And when you related seeing the pictures did you make a genre distinction? Probably not.

My criteria for categorizing a film as blaxploitation is straightforward. I define the films as theatrically released motion pictures (between 1970-1980) that were conceived, green lit and first and foremost promoted to inner city black audiences. Using this broad definition, which I more thoroughly outline in Blaxploitation Cinema, many “gray area” pictures make the cut. Many film fans don’t believe that Mahogany and Greased Lightening, should be in the book, but I beg to differ—and it’s an ongoing argument!

Blaxploitation films are really “exploitation” films; that’s where the hybrid name comes from. They’re low budget pictures made for the Drive-In and “downtown” theater market. Black people experienced films like The Big Doll House and Women in Cages as a Blaxploitation film—not as a Woman in Prison film. Additionally blaxploitation films were often shown on Double Bills. This under-discussed approach to distribution should also be considered. If you went to the theater to see two pictures and one was clearly defined as Blaxploitation (40 of the films have the word “black” in the title by the way), what was your experience of the accompanying film? Why were they paired? And when you related seeing the pictures did you make a genre distinction? Probably not.

Absolutely: Viva Roger Corman! He along with producer Cirio Santiago are responsible for putting the Philippine movie market on the international map. While American producers were racking their brains trying to find cheap places to make movies, the Philippines were sitting there all the time! It’s a gorgeous country with beautiful vistas, landscapes and people—and it’s tropical.

When I interviewed Cirio Santiago for my book I was amazed by both the scope of his work and his unusual humility. He produced at least one film a year in the Philippines for thirty years in a row. His name is on more than 100 films. Some of the many great titles he produced in the Philippines include The Muthers, Savage!, Ebony, Ivory & Jade and the fantastic TNT Jackson (both his personal favorite and mine).

Good question! Actors did not want to talk to me. Many of them were embarrassed by their participation in the genre and didn’t want to revisit it. They had a revised opinion about these pictures and many felt that they were underpaid and misrepresented. It was only after the actors refused to talk to me that I focused on the directors. I said to myself: “If I can get five directors to talk that would be great.” Then I kept going and got ten—before the publication deadline. I was so grateful that they were still around—thirty years had passed—and were happy to take the time to let me sit down and interview them.

In the end, the decision by the actors not to discuss the films worked in my favor. The directors were the ones that had the real stories. They could talk expansively about the creative process; writing, directing, and casting, but they could also talk about things that the actors weren’t involved in like movie studio politics, budgets, marketing and the executive take on the genre.

People remain divided on the merits of blaxploitation films and young people are easily offended. At one of my university lectures I actually saw a young white girl burst into tears when I projected a group of posters with the N-word in the title. It was a shock to her system. I think the younger generation just doesn’t get it. They don’t understand how Hollywood got away with releasing films with titles like The Soul of Nigger Charley, The Six Thousand Dollar Nigger or Run, Nigger, Run.

What students learn from my lectures is that the choice to use the N-word in film titles was made by African Americans—not white people. It’s not so different than the use of the word in Hip Hop. It’s taking ownership of the word away from white people and making it our own. Actor Fred Williamson freely admits that his choice to use the N-word in his film titles was calculated: “… that was sure to get them interested in the movie,” he says. “I knew what I was doing: it helped sell tickets.”

Oh, it was fantastic! It was a great learning experience for me because I knew very little about Brazil, the people, the country and the culture. What I discovered was that they have as big a racial divide as America does. Consequently, their films have gone through a similar evolution. They were the last country to abolish slavery so they have a pronounced caste system. Brown and black Brazilians are on the low end of the totem pole while white skinned Brazilians are the politicians, entrepreneurs and entertainment industry stars.

Brazil was also a great place to talk about the films because they saw them at the time of their original release. They got American import films dubbed in Portuguese, so they were as familiar with Coffy, Shaft and Super Fly as I was. And blaxploitation did the same thing for black and brown Brazilians as it did for Americans: it allowed them the vicarious thrill of being successful—according to their own rules.

The broad based appeal of the films with Brazilian audiences was profoundly brought home to me when I spoke at the Odeon Theater in Sao Paulo. It’s one of the country’s most important culture venues and the energy was incredible: there wasn’t an empty seat in the house—and it seat 5,000! Just talking about Brazil makes me want to go back. Even though there were communication challenges (I had an interpreter), and it was difficult for me to negotiate transportation (I was terrified of being late for all the important engagements they had booked me for) the people were absolutely wonderful to me. I keep in contact with many Brazilian fans. It was an honor.

Absolutely! I’ve always made this case. Blaxploitation films provided a great forum for black music talent. Imagine Super Fly without Curtis Mayfied’s incredible soundtrack album or Shaft without that amazing Grammy and Oscar-winning Isaac Hayes song “Theme From Shaft.” Whether the characters are making love, strutting down the street, or engaged in a street corner brawl, music is essential to the mise en scene of blaxploitation.

There’s no question that Super Fly is the most fully realized blaxploitation soundtrack album. “Super Fly,” “Freddie’s Dead” and “Pusherman” were all hits and they are just as engaging and topical as they were when they were released. My favorite soundtrack from the era is probably Marvin Gaye’s Trouble Man. It’s heavy on instrumental tracks but it’s hauntingly beautiful. Also stellar is Roy Ayers’ Coffy, James Brown’s Black Caesar and Barry White’s Together Brothers.

There's another book on the genre called That's Blaxploitation! Roots of the Baadasssss 'Tude, by Darius James. It takes a different approach than yours do, it's both entertaining and quite odd. Have you read it and if so, what are your opinions of it?

That’s a fun book; more one person’s take on the genre than an overview. I met Darius at a Blaxploitation symposium at The Schomburg Center for African American Research here in NYC. We both gave lectures and, afterwards, we chatted: he’s quite a character!

Our books are different: his is a personal take, mine is a distanced overview. Don’t get me wrong, Blaxploitation Cinema contains many barbs and cutting observations, but the story of blaxploitation cinema is not my story: I'm just the messenger. My desire is to present context and information. I encourage the reader to see the films and draw their own conclusions.

That’s a fun book; more one person’s take on the genre than an overview. I met Darius at a Blaxploitation symposium at The Schomburg Center for African American Research here in NYC. We both gave lectures and, afterwards, we chatted: he’s quite a character!

Our books are different: his is a personal take, mine is a distanced overview. Don’t get me wrong, Blaxploitation Cinema contains many barbs and cutting observations, but the story of blaxploitation cinema is not my story: I'm just the messenger. My desire is to present context and information. I encourage the reader to see the films and draw their own conclusions.

Many people, inside and outside of the film industry, find the term “blaxploitation” derogatory. Fred Williamson has been one of the most vocal opponents to the labeling and categorization. He says if Death Wish isn’t called “whitesploitation” why should Black Caesar be called blaxploitation. He’s got a good case but it’s a case I won’t be making.

The director’s that didn’t want to speak to me didn’t want their films labeled “blaxploitation”—even if they were. They were revisionists. I understand where they’re coming from but I don’t agree with the basic premise that the term “blaxploitation” is disrespectful or exploitative. We’ll agree to disagree!

I was a guest commentator on five episodes of a TV series called Unsung Hollywood here in America. Unsung has been running for ten years on the African American network TV One. Unsung spends an hour looking at African American achievement in the entertainment industry. I met many of the major players in front of and behind the scenes of blaxploitation when I was filming episodes.

I remember when I did the Richard Roundtree episode two of his relatives were waiting in the green room for their turn to go before the cameras. They were great older people with their own unique stories and they were so proud of Roundtree and his accomplishments. They made a bigger impression on me than Richard himself!

Only from the directors. They loved their interviews and they love the book and the fact that I presented them as more than working professions: to me they are an important part of American film history. Jammaa Fanaka (Penitentiary) was great. So was Robert A. Endelson (Fight For Your Life) and Larry Cohen (Black Caesar). Arthur Marks (Detroit 9000) told me that his grandchildren can’t believe that he’s worthy of being in a serious book about cinema!

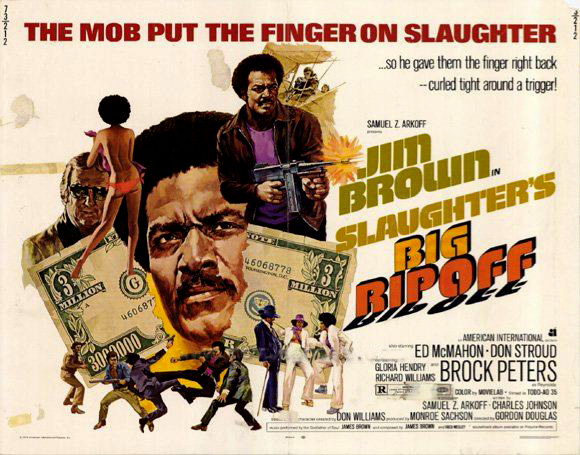

Fred Williamson and Jim Brown are the equivalent of Pam and both were just as big as Pam at the Box Office. Brown’s Slaughter was the No. 1 film in America and it was followed by a sequel: Slaughter’s Big Rip Off. He was an athlete who photographed well and had a cool laid back air about him. Fred Williamson is a movie star on a par with Tom Cruise. He’s an engaging commodity; a multi-talented actor/producer/writer who played in Westerns, comedies, dramas and even an engaging African American take on the James Bond franchise—called That Man Bolt. Both of these men are superior talents and genuine African American movie stars. What they did meant a lot to black audiences at the time: and it still does.

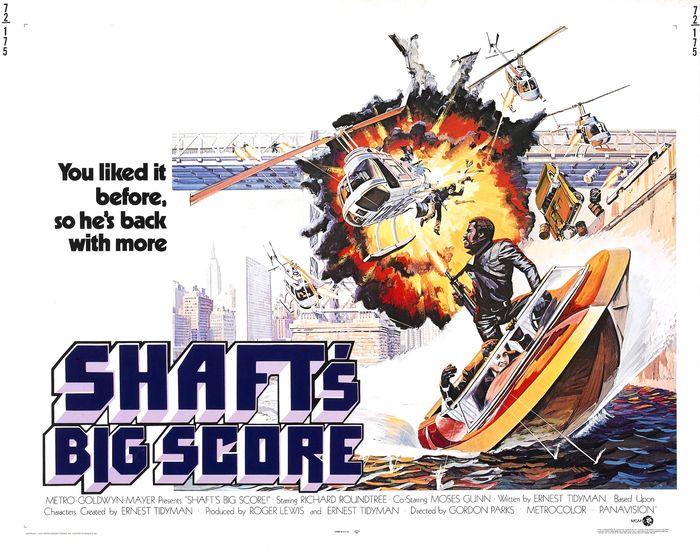

Super Fly is the best. Acting, writing, music, atmosphere, intent. The main character wants to get out of the drug trade. My personal favorite is Coffy. It’s an anti hero vigilante justice tale that hit No. 1 Variety’s Top Grossing Box Office List (just as popular with white audiences as with African Americans) and made Pam Grier a star. It’s bombastic, outrageous, stunning to behold and clever. A downbeat film (no happy ending here) with a message. Simple and profound.

Idris Elba would be perfect for the part (even if he is British!) He’s fantastic: a good actor with charm and charisma and he’s already displayed his athletic prowess on film.. Although I'm attached to the originals, I stand behind re-making films from the genre. If Hollywood wants to pay for a brand new updated version, that’s great! Much has changed and that can all be worked into a retelling. I’ll keep my fingers crossed.

Best: Coffy, Super Fly, Shaft’s Big Score!, Top of the Heap, Black Caesar, in that order.

Worst; (but still fun as camp): The Guy From Harlem, Miss Melody Jones, Speeding Up Time, Mean Mother, The Bus is Coming, in that order.

I'm a regular contributor to several cinema websites and I continue to be a consultant on the genre: both on the lecture circuit and behind the scenes. Currently I'm very excited about two screenplays that I’ve written. I have an agent in Los Angeles and he’s shopping them. It really is my best writing: incorporating my love and knowledge of cinema, my personal experiences, and my passions and inclinations. It’s my hope to see you soon Anders: at a theater near you!